Repressing democracy online in Asia, one law at a time

Recent reports indicate that Myanmar’s military junta is about to pass a highly restrictive cybersecurity law, an earlier version of which already drew massive international and national criticism. this law would effectively close any remaining online civic space in the country and place private service providers at the will of the junta. the Cambodian government also recently imposed a decree that establishes an internet gateway, a mechanism that gives the Cambodian authorities the capacity to block any content they deem inappropriate.

These are just two examples on a long list of laws seeking to restrict digital rights and the freedom of expression in the Asia Pacific region. Some of the most prominent examples include the Digital Security Act (DSA) in Bangladesh, the Cybersecurity Law in Thailand, and the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act in Singapore.. Although Covid-19 has been used as a pretence to accelerate the approval of some of these laws--such as in the case of the re-introduction of the AFNA in Malaysia--this phenomenon precedes the pandemic. Since 2018, at least 15 countries1 in the Asia Pacific region have passed, or are about to pass, legislation that restricts digital rights or that poses a serious threat to civil space and discourse online in some way.

While the alleged justifications for these restrictions include things like the need to combat disinformation (in Malaysia) or to enhance cybersecurity (such as in Thailand), or to more generally protect citizens against the dangers of digital content (as in Pakistan or Kazakhstan), there are serious concerns.

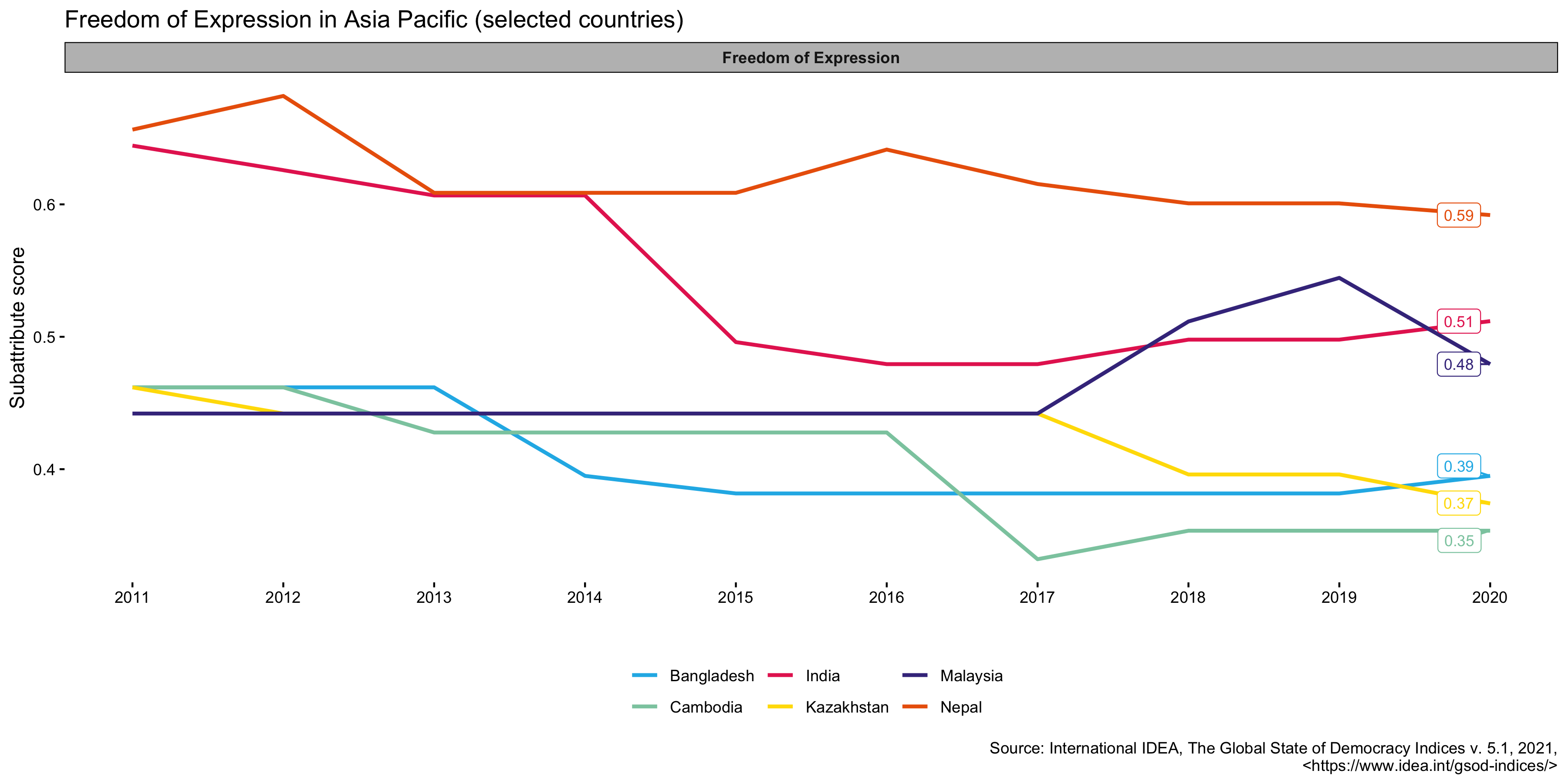

Firstly, these laws bestow nearly unchecked power on authorities to decide unilaterally what is and is not true and what could signify a harm to society, all without due diligence. Research shows that such power becomes a threat to civic discourse online and to two key attributes of democracy, Freedom of Expression and Media Integrity.

Secondly, these laws often violate the principle of liability protection for service providers, a key to internet openness. Enshrined in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of the US, liability protection shelters internet service providers, or their employees, from bearing legal responsibility (with some exceptions) for the content published using their services. The principle is not free from controversy and debate; yet, it remains a key aspect of US legislation and is now being streamlined further by the European Union’s Digital Service Act. Ignoring this principle means that private companies become the executors of state repression online. Now, Twitter, Google or Meta face the dilemma of complying with online repression or jeopardizing the safety of their staff in these countries.

Ultimately, these legal attacks further close civic space in Asia Pacific, a key component of healthy democracies. Although online debate and dissent opened new spaces for activism and opposition, it is now becoming the ground of increasing repression all over the region. The battle to defend democracy is also being fought on the internet, and online repression laws are becoming a favourite weapon of the enemies of democracy.

About the author:

Alberto Fernandez Gibaja's work focuses on the crossroads between Political Participation, innovation and technology.

To access the original publication, please click here